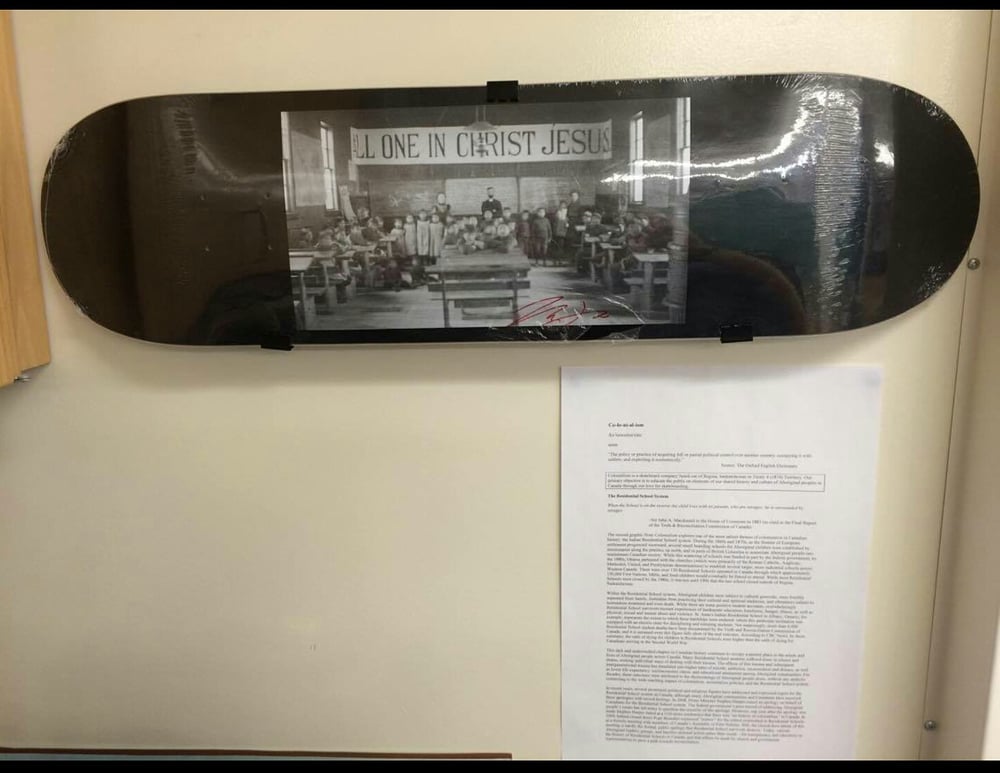

Residential School deck

The Residential School System

When the School is on the reserve the child lives with its parents, who are savages; he is surrounded by savages.

−Sir John A. Macdonald to the House of Commons in 1883 (as cited in the Final Report of the Truth & Reconciliation Commission of Canada)

The second graphic from Colonialism explores one of the most salient themes of colonization in Canadian history: the Indian Residential School system. During the 1860s and 1870s, as the frontier of European settlement progressed westward, several small boarding schools for Aboriginal children were established by missionaries along the prairies, up north, and in parts of British Columbia to assimilate Aboriginal people into mainstream Canadian society. While this scattering of schools was funded in part by the federal government, by the 1880s, Ottawa partnered with the churches (which were primarily of the Roman Catholic, Anglican, Methodist, United, and Presbyterian denominations) to establish several larger, more industrial schools across Western Canada. There were over 130 Residential Schools operated in Canada through which approximately 150,000 First Nations, Métis, and Inuit children would eventually be forced to attend. While most Residential Schools were closed by the 1980s, it was not until 1996 that the last school closed outside of Regina, Saskatchewan.

Within the Residential School system, Aboriginal children were subject to cultural genocide, were forcibly separated from family, forbidden from practicing their cultural and spiritual traditions, and oftentimes subject to horrendous treatment and even death. While there are some positive student accounts, overwhelmingly Residential School survivors recount experiences of inadequate education, loneliness, hunger, illness, as well as physical, sexual and mental abuse and violence. St. Anne's Indian Residential School in Albany, Ontario, for example, represents the extent to which these hardships were endured, where this particular institution was equipped with an electric chair for disciplining and torturing students. Not surprisingly, more than 6,000 Residential School student deaths have been documented by the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada, and it is assumed even this figure falls short of the real outcome. According to CBC News, by these estimates, the odds of dying for children in Residential Schools were higher than the odds of dying for Canadians serving in the Second World War.

This dark and understudied chapter in Canadian history continues to occupy a painful place in the minds and lives of Aboriginal people across Canada. Many Residential School students suffered alone in silence and shame, seeking individual ways of dealing with their trauma. The effects of this trauma and subsequent intergenerational trauma has translated into higher rates of suicide, addiction, incarceration and disease, as well as lower life expectancy, socioeconomic status, and educational attainment among Aboriginal communities. For decades, these outcomes were attributed to the shortcomings of Aboriginal people alone, without any analysis connecting to the wide reaching impact of colonialism, assimilation policies, and the Residential School system.

In recent years, several prominent political and religious figures have addressed and expressed regret for the Residential School system in Canada, although many Aboriginal communities and Canadians have received these apologies with mixed feelings. In 2008, Prime Minister Stephen Harper issued an apology on behalf of Canadians for the Residential School system. The federal government’s poor record of addressing Aboriginal people’s issues has led many to question the sincerity of this apology. However, one year after the apology was made Stephen Harper stated at a G20 news conference that there was “no history of colonialism” in Canada. In 2009, behind closed doors Pope Benedict expressed “sorrow” for the crimes committed in Residential Schools at a historic meeting with members of Canada’s Assembly of First Nations. Still, the closed-door nature of this meeting is hardly the formal, public apology that Residential School survivors deserve. Today, various Aboriginal leaders, groups, and families demand action rather than words – for transparency and education on the history of Residential Schools in Canada, and that efforts be made by church and government representatives to pave a path towards reconciliation.